Writer’s Corner: Listening to Your Characters

Posted: March 3, 2025 Filed under: Books, Character Development, Dialogue, Fiction, WordCrafter Press, Writer's Corner, Writing, Writing Process | Tags: characters, Kaye Lynne Booth, Writer's Corner, Writing Process, Writing to be Read 11 CommentsDo your characters talk to you? I’ve met authors who say, “How could they? They aren’t real. They are fictional characters which I made up.” But if you are in touch with the characters which you created, I don’t see how they could not talk to you. I believe these authors who claim to not hear their characters maybe just aren’t listening.

My characters talk to me and help guide my stories. My characters refuse to stay silent. I don’t actually hear or see them, of course, but they do talk to me in my head. I hear the dialog as it goes on the page, and they are sure to tell me if I get it wrong.

I recall when this first happened while writing my first novel, Delilah. There was a scene in the story which I recognized wasn’t working, but I couldn’t figure out why. I sat in front of my computer re-reading the chapter, which was the dialog of a conversation between Delilah and another character. I said to myself, “Something isn’t right here, but what is it?” And a voice in my head replied, “I wouldn’t react that way.” Re-reading it once more, I realized that the voice of Delilah was right. I had my character reacting in a certain way because it was necessary in order for events in the future to occur, but it wasn’t a reaction that would come naturally from the character I had created. I rewrote the conversation, changing Delilah’s reaction to be true to her character, and it changed the direction of the story, completely. It required extensive revisions throughout the story, including total rewrites of the chapters which came after that scene, but it made it a much better tale than the one I had planned to write, so it was better for the story in the long run.

While writing Sarah, my character hijacked a conversation between her, Big Nose Kate, and a high-society woman, and her opinions on corsets set off an unexpected suffrage movement in Glenwood Springs, complete with a protest and corset burning. When I began writing the story, I had no idea that this would happen in the book, but when I placed the words upon the page, it all just clicked, and I said, “Oh, yeah”.

With both books in my Time Travel Adventure series every chapter is paired with a song. All of Amaryllis’ music was done by The Pretty Reckless, which first inspired her character. But for LeRoy and the other characters who were given P.O.V. in the second book, the music from various artists were used. As I perused the radio stations, searching for just the right song for each chapter. I can think of several times when a song I wasn’t familiar with would come on and LeRoy would give my mind a nudge that said, “Listen to this song.” Paying attention to what he had to say, I focused on the music, listening to the lyrics, and found that the song was perfect for a specific chapter, and the song ended up in the book and on LeRoy’s play list.

Of course, I’m aware that my character’s voices are really voices from my own subconscious, because every one of the characters I create are a part of me. But being in touch with them enough to them to hear their voices in my head makes them feel more like old friends and helps me bring the story to life.

We all have the ability to hear our characters if we’ll only listen to what they have to say. I’ve found that their observations are right on the money. My stories turn out better for listening to them. So, tell me. Do you listen to your characters?

About Kaye Lynne Booth

For Kaye Lynne Booth, writing is a passion. Kaye Lynne is an author with published short fiction and poetry, both online and in print, including her short story collection, Last Call and Other Short Fiction; and her paranormal mystery novella, Hidden Secrets; Books 1 & 2 of her Women in the West adventure series, Delilah and Sarah, and her Time-Travel Adventure novel, The Rock Star & The Outlaw,as well as her poetry collection, Small Wonders and The D.I.Y. Author writing resource. Kaye holds a dual M.F.A. degree in Creative Writing with emphasis in genre fiction and screenwriting, and an M.A. in publishing. Kaye Lynne is the founder of WordCrafter Quality Writing & Author Services and WordCrafter Press. She also maintains an authors’ blog and website, Writing to be Read, where she publishes content of interest in the literary world.

___________________________________________

Did you know you can sponsor your favorite blog series or even a single post with an advertisement for your book? Stop by the WtbR Sponsor Page and let me advertise your book, or you can make a donation to Writing to be Read for as little as a cup of coffee, If you’d like to show your support for this author and WordCrafter Press.

______________________________________

This segment of “Writer’s Corner” is sponsored by the My Backyard Friends Kid’s Book Series and WordCrafter Press.

The My Backyard Friends kid’s book series is inspired by the birds and animals that visit the author Kaye Lynne Booth’s mountain home. Beautiful illustrations by children’s author, poet, and illustrator, Robbie Cheadle, bring the unique voices of the animal characters to life.

Get Your Copy Now.

Heather Hummingbird Makes a New Friend (Ages 3-5): https://books2read.com/MBF-HeatherHummingbird

Timothy Turtle Discovers Jellybeans (Ages 3-5): https://books2read.com/MBF-TimothyTurtle

Charlie Chickadee Gets a New Home (Ages 6-8): https://books2read.com/MBF-CharlieChickadee

Writer’s Corner: Word Choices

Posted: July 1, 2024 Filed under: AI Technology, Books, Character Development, Dialogue, Fiction, Setting, The Human Condition, Time travel, Voice, Western, WordCrafter Press | Tags: AI Technology, Dialogue, Editing, Speech, Voice, Word Choices, Writer's Corner, Writing to be Read 17 CommentsI don’t need MS Word to tell me that my language might be offensive. That’s me. I use offensive language, usually on purpose, for effect because I want to be offensive, or just because it is what my character would say. Of course, I’m not writing for a YA or younger audience. I would want curse words to be pointed out and questioned, if that were the case.

I cuss. Most of the people I know cuss. Even religious folk have been known to issue a curse or two. If I feel the reaction to a situation would be an issued expletive, then my character will issue it. That doesn’t mean that all my characters are potty mouths, but when a curse is in order, they throw it out there, and I believe it is appropriate in certain situations, and also more realistic.

Even if my protagonist isn’t a curser, like Delilah, who uses expletives such as dagnabbit, the people around her do, so my books do contain some cursing. I don’t feel like a story set on the western frontier, would be true to the period or the frontier culture.

Likewise, the modern day Las Vegas culture in the music circles involves drugs, sex, and rock-and-roll, so naturally my character, Amaryllis, in The Rock Star & The Outlaw is involved in all of that and more, and her language often isn’t ladylike. Even so, I try not to let her get carried away with the curse words. And Sarah deals with the issues of prejudice and sexism, and the language in the story reflects the prejudices of the times, whether the AI editor in MS Word likes it or not.

But my villains often have mouths so dirty even their own mothers wouldn’t kiss them. Respect for women or lack thereof is often indicated in the way a man refers to women. If a character lacks respect for women, which many male villians do, then their language when referring to them may be less than flattering. After all, the way a character speaks is one of the things readers use to clue them in to what a character is like, and then decide if they are a character they should like, or not.

Another speech trait which I use often is the improper use of the English language. In the old west, many people were not educated and used words such as ‘ain’t’ or they cut off the ‘g’ in ‘ing’ words. In Delilah, one of things she strived for was to speak more properly after meeting the Mormon woman, Marta, who was a natural born school teacher and corrected Delilah’s speech automatically out of habit. Many of the less savory characters in the Women in the West adventure series, clue readers into their ignorance by the way they speak. I reckon that’s what I do it fer. These are purposeful misspellin’s that drive my AI spell-check crazy.

Many of my western characters are representitive of the many immigrants who made the U.S. into the melting pot that it is known to be. They speak in different dialects to differentiate them from other characters, which gives them colorful speech that is recogizable without adding dialog tags. In Sarah, Lillian Alura Bennett is one such character, who happens to be an Irish madam at a bordello in Glenwood Springs. And in The Rock Star & The Outlaw, the Mexican dialect of Juan Montoya leaves no question when he is speaking.

In Delilah, I had the opposite problem as the character of Dancing Falcon was a young Indian boy, who had been taught to speak English at the Indian agency with a strict teacher, so his speech is almost too proper, which made his speech sound very formal in places. One of the comments from a beta reader was that no one talks like that, so I went back when revising and added in a place where he talks about his time on the reservation and his schooling experience, to explain why he spoke that way to readers. The point being that a characters speech should reveal something about them, as well as making them identifiable.

It was really fun to create the characters in the My Backyard Friends kid’s book series, which is based on the birds and animals which visit my yard in the Colorado mountains. Katy Cat is a bit of a diva, kind of stuck up, and thinks she’s better than everyone else. She’s willing to help out Timothy Turtle as long as it doesn’t inconvenience her too much. I relayed this information in the way she swishes her tail, (body language), and in the way she talks with a bit of attitude. Heather Hummingbird has a lot of energy, so she talks really fast and rarely perches for more than a few seconds at a time. Charlie Chickadee is a young bird on his own for the first time, so I made him a bit niave. The things he says reveals this more than the way that he says it.

Other reasons an author might make the character’s or even the narrator’s voice a bit quirky is because it is the author’s voice coming through. (You know the voice English teachers are telling you to find? Yep. That one.) To an extent, this is true for me. My own speech is usually rather blunt and to the point, and so are my characters’. I don’t use a lot of colorful purple prose, instead calling it like I see it. Many of my protagonists are the same way. Delilah says what’s on her mind and she doesn’t beat around the bush. Sarah, too, tends to speak before she considers the way her words will be taken.

AI editors don’t understand this, and so variants in speech are often marked as needing correction, when in fact, they are purposeful. This is why, just running through your story with an AI editor is never enough. But there are times when human editors don’t get it either. Kevin J. Anderson tells a story about submitting a book to a traditional publisher who turned it over to a novice editor who corrected all the little quirks that revealed his voice and marked his manuscript up until it looked like nothing but red scribbles. That’s when you know that an editor isn’t a good match for you. Kevin politely refused to work with that editor and they assigned him another one. That’s why it’s important to have an editor that gets you and your voice, and understands the nuances of your character’s dialog.

Finding the right editor isn’t always easy, especially if funds are tight. Many editors will offer a free edit of the first ten pages, or even the first chapter so you can fell them out and find out if they are right for you and your story. I wouldn’t go with any editor who doesn’t offer this, and of course, I offer it through Write it Right Quality Editing Services. Any editor worth their salt will understand that they must be able to differentiate between mistakes and purposful word choices.

___________________________________________

About Kaye Lynne Booth

For Kaye Lynne Booth, writing is a passion. Kaye Lynne is an author with published short fiction and poetry, both online and in print, including her short story collection, Last Call and Other Short Fiction; and her paranormal mystery novella, Hidden Secrets; Books 1 & 2 of her Women in the West adventure series, Delilah and Sarah, and her Time-Travel Adventure novel, The Rock Star & The Outlaw. Kaye holds a dual M.F.A. degree in Creative Writing with emphasis in genre fiction and screenwriting, and an M.A. in publishing. Kaye Lynne is the founder of WordCrafter Quality Writing & Author Services and WordCrafter Press. She also maintains an authors’ blog and website, Writing to be Read, where she publishes content of interest in the literary world.

____________________

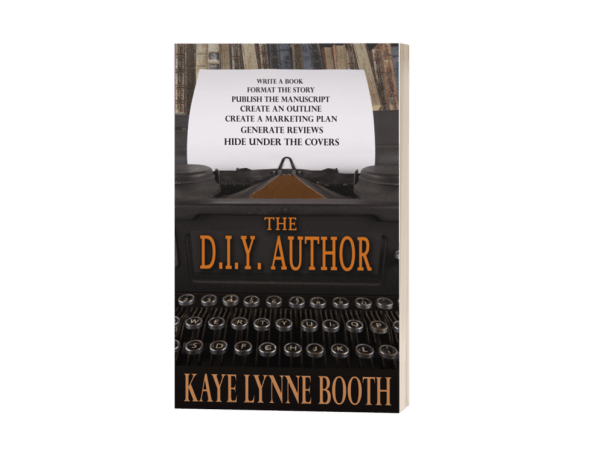

This segment of “Writer’s Corner” is sponsored by The D.I.Y. Author and WordCrafter Press.

Being an author today is more than just writing the book. Authors in this digital age have more opportunities than ever before. Whether you pursue independent or traditional publishing models, or a combination of the two, being an author involves not only writing, but often, the publishing and marketing of the book.

In this writer’s reference guide, multi-genre author and independent publisher, Kaye Lynne Booth shares her knowledge and experiences and the tools, books, references and sites to help you learn the business of being an author.

Topics Include:

Becoming Prolific

Writing Tools

Outlining

Making Quality a Priority

Publishing Models & Trends

Marketing Your Book

Book Covers & Blurbs

Book Events—In Person & Virtual

And more…

Pre-Order your copy today: https://books2read.com/The-DIY-Author

Craft and Practice with Jeff Bowles – Narrators of a Different Color

Posted: May 19, 2021 Filed under: Character Development, Craft and Practice, Dialogue, Fiction, Point of View, Story Telling Methods, Tense, Voice, Writing | Tags: Craft and Practice, Dialogue, Jeff Bowles, narration, Point of View, writing advice, Writing Tips, Writing to be Read Leave a commentEach month, writer Jeff Bowles offers practical tips for improving, sharpening, and selling your writing. Welcome to your monthly discussion on Craft and Practice.

There’s an entire school of thought behind the use of standard third-person perspective in narrative fiction. Often enough, beginning writers are encouraged to see it as their go-to, which isn’t horrible advice. Let’s do a quick POV lesson, in case your memory is hazy.

First-person: I walked to the lake.

Second-person: You walked to the lake.

Third-Person: He walked to the lake.

Conventional wisdom says most readers stomach lucky number three best. I think that might be a load of hogwash, but let’s assume it’s 100% correct. What would be the benefit of writing fiction—or creative nonfiction, for that matter—from a quote, unquote “nontraditional” perspective? Your own edification, right? And maybe something else.

Third-person is the norm because it provides helpful breathing room between us and our readers. It’s easy to tell a story this way, natural. We’re used to it, having read it a million times before. By the same token, I have noticed it’s become increasingly more common for storytellers to dabble in other modes. First or second-person, past or present tense, limited omniscience or full-blown mind-of-God territory. First-person present tense, by the way, is notoriously apt to cause chaos.

“I write on the blog post for a bit, and then I check my email. It occurs to me I’ve never met a sultan of Saudi Arabia, so it’s possible these diet pills are phony. Oh well. I chuck them in the trash and head outside to clear my mind. It smells like a forest fire out here. Hey, what gives?”

This is stream of consciousness stuff, easy to write but difficult and unwieldy to beat into proper shape. All the verbiage points to me, me, me, now, now, now. It can get same-same after a while, difficult to chew through. Not always, but often enough.

I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt and assume your new forest fire/phony diet pill story is perfectly well written, thank you very much. You did the job, tale told effectively, end of discussion. In that case, one crucial question comes to mind. Is your narrator any fun to read?

What do you mean, what do I mean? What’s a fun narrator supposed to sound like? Well, I guess they can be any of the following: idiosyncratic, faulty, confident, psychotic, mentally sound, likable, unlikable, funny, unfunny, jaded, naïve, a super focal lens, an individual with something to say, a personality worth delving into.

Maybe you’ve never considered it this way, but in my humble estimation, narration of this kind is a blank check. Most things worth achieving sound unlikely at first. Think of it like speed dating. You known instantly upon sitting across from someone whether or not you’d enjoy their company. Is your speed-dater worth engaging in conversation? Are they fun to listen to?

Gut check time. How well do you write dialogue? I only ask because I’ve realized throughout the years not everyone is as keen on it as I am. Sharp and amusing with zero fat left to trim, that’s my favorite kind. But what’s yours? Informative but not dull? Wacky and a bit irredeemable? More importantly, do you think you could extend a few lines of it to encompass an entire story? I’m willing to bet you can.

The simple truth is most writers create bland characters by default. Not you, of course. Perish the thought. Mentors and teachers might encourage us to pre-fill character sheets or go to public places and write down snatches of conversation we hear. I’m not saying that’s bad advice, but I can confidently tell you it’s more efficient and effective to let characters tell us who they are rather than to impose our sizable wills upon them. Don’t bloat yourself up with too much preparation. On the fly, hit the page and let your creations speak to you. A little honest individuality is enough to distinguish your work from the work of others, and that’s a good thing.

Rule makers have tried to enter this arena, but I don’t think they’ve done a great job setting any concrete prescriptive measures. Is addressing your reader directly breaking the fourth wall? No, not really. If you think about it, first-person narration divorced from context is unnatural anyway. It was much more common in centuries past for authors to speak to their readers through narration. As we discussed earlier, stability is easy to achieve by providing a little breathing room. This is a blank check, remember? Anything and everything is achievable, provided you’ve got the skills to stick the landing. That’s the thing about experts. If they tell you something can be done, they’re most certainly right. If they tell you it can’t, they’re most certainly wrong.

Style remains essential in this domain. My final advice is this: If you’re currently working on something you’ve written in first-person, try playing with your style a little, write it like you’d write some nice extended dialogue, just as far as you’re comfortable, nothing too crazy—unless you like crazy. You might just surprise yourself. Scratch that. Your narrator might surprise you.

Don’t be stiff or formal. Get into the nitty gritty and pour a serious helping of personality gravy on those otherwise boring and bland mashed ‘taters.

On that note…

See you next time, everyone. Have an awesome May, will you?

Jeff Bowles is a science fiction and horror writer from the mountains of Colorado. The best of his outrageous and imaginative work can be found in God’s Body: Book One – The Fall, Godling and Other Paint Stories, Fear and Loathing in Las Cruces, and Brave New Multiverse. He has published work in magazines and anthologies like PodCastle, Tales from the Canyons of the Damned, the Threepenny Review, and Dark Moon Digest. Jeff earned his Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing at Western State Colorado University. He currently lives in the high-altitude Pikes Peak region, where he dreams strange dreams and spends far too much time under the stars. Jeff’s new novel, Love/Madness/Demon, is available on Amazon now!

Check out Jeff Bowles Central on YouTube – Movies – Video Games – Music – So Much More!

Want to be sure not to miss any of Craft and Practice with Jeff Bowles segments? Subscribe to Writing to be Read for e-mail notifications whenever new content is posted or follow WtbR on WordPress

The Essence of Writing Good Dialogue

Posted: April 15, 2020 Filed under: Dialogue, Fiction, Writing, Writing Tips | Tags: Dialog, Jeff Bowels, Writing, Writing Tips, Writing to be Read 3 CommentsIt’s not what you say. It’s the way you say it.

by Jeff Bowles

I love good dialogue. In fact, it may be my favorite thing about reading a book or watching a truly excellent film. Many serious writers will tell you that it’s an important tool in the author’s toolkit, but that it is by no means the most essential. I respectfully disagree. I say good dialogue can elevate your writing like nothing else. After all, it’s not what you say. It’s the way you say it.

Looking back, I realize I’ve always been polishing up my ability to generate interesting, gripping, or just plain funny dialogue. I self-studied writers and filmmakers who made it a priority in their storytelling, folks like Douglass Adams, Elmore Leonard, and Quentin Tarantino. I read a lot of Marvel and DC comic books, which as you may or may not know, are almost completely composed of dialogue. I don’t know why it mattered so much to me, but I absolutely lit up whenever characters interacted with each other in snappy and surprising ways. I still light up when I read, see, or hear the good stuff, and maybe I can’t speak for everyone on this, but when was the last time you saw a well-produced Shakespeare production and thought to yourself, Gosh, that guy just couldn’t write people to save his life?

That’s the key. People live in dialogue. Not in long winded descriptions or deep internal navel gazing. Characters come to life in their interactions with each other. You could say it’s the one thing that makes them leap off the page. It’s how people work in real life, too. Which is to say, without conversation, people tend not to work at all. Sit together with someone in an awkward silence long enough and you’ll know exactly what I mean.

When it comes to short stories and novels, good dialogue is essential. Sure, you’re a master of scene setting and description, but do all your characters seem to communicate like wooden B-movie stereotypes? Or another problem many writers have, have you noticed you’re timid on engaging your readers with dialogue, and so you tend to rely on big blocks of text to get your message across? Scene setting, subtle character development, basic point-to-point plotting, visceral sense engagement and description, and basic personal style may be the rhythm of the music we call fiction, but truly inspiring dialogue is quite essentially the melody.

If you think about it, you don’t even really know characters until they open their mouths. If you struggle with dialogue, or if you’re just looking to brush up on the basics, there are a few exercises you can employ. One, of course, is to go to a public place and listen to people converse in real time. Admittedly, not really a viable option during Coronavirus lockdown, but you can easily work this exercise from the comfort of your own home. Tune into some reality TV, or simply listen to the conversations your family have. Write down every word verbatim, if you can. You’ll notice that people tend to speak in a pretty roundabout way, with lots of umms and starts and stops thrown in the mix.

Good dialogue should contain elements of realistic conversation, but you also need to focus it like a laser beam. If you were to write a scene in which people talk like they do in real life, you’d end up with so many pauses, ellipses, and false starts it’d drive your readers nuts.

“Hi, Jim, how’d work go?”

“Oh, you know, I don’t know … the boss, he’s real … umm … I don’t know, he’s real pushy when it comes to … when it comes to, uh … oh, I don’t know”

Doesn’t really flow all that well, does it? May I present the alternative that what you’re going for with good character interactions isn’t so much realism as pointed randomness. That is to say, make an effort to produce dialogue that cracks like a whip, pops and snaps like lightning. Only make sure also that it’s random enough no one can accuse you of stiffly holding your reader’s hand.

“Hi, Jim, how’d work go?”

“Ah, you know, the boss … ever get the feeling some people’s neckties are on too tight?”

“Uh-oh. I know that tone. He got pushy again, didn’t he?”

“Pushy? I haven’t slept in weeks. Pretty sure I had a waking dream while filing a client’s paperwork today. By the way, if the office calls asking why I’ve suggested one Dana Baker should just hit the clown on the nose and fly away on his trusted dragon, I’m not in.”

Also, don’t be afraid to surprise yourself. If you’re surprised by your writing, you can guarantee your readers will be, too. Zig instead of zag when you approach character interactions. Also, try producing more dialogue on the page than you’re used to. A lot of readers just kind of sift through text blocks anyway. They consider the dialogue the real meaty parts. Sad, but I think it is true. Readers are less interested in what’s happening now than in what happens next. You can fuel that burning need to find out.

Here’s something else you may not have considered. The first true novel written in the English language was likely published sometime in the 16th century, or thereabouts. A couple centuries later in the Victorian era, the novel had exploded in popularity, and that period is still a gold mine as far as writers who produced work we’re reading to this day. In all the time since, our concept of good narrative fiction has gotten lighter, not heavier.

Have you ever been chewing your way through a Victorian novel and thought to yourself, Why’s it taking this lady so long to get out of her house? Well, it’s because back then, the form and function of the novel was to in some fashion reproduce life. Entertainment is its form and function in the year 2020, because these days authors have to compete with film, television, internet memes, video games, just about anything that’s loud, fast, and gets its point across in seconds flat.

Unfortunately, you are therefore also competing with shortened attention spans across the globe. Do yourself a favor, don’t shirk your duty to write super fun, super engaging dialogue. It can save even the dullest story. Well, maybe not the dullest. Need something more specific? Well, for one, make sure all your dialogue tags (or at least most of them) are of the simple, he said, she said variety. Very few of these said-bookisms you’ve heard so much about.

Also, try bouncing back and forth between characters like they’re playing verbal tennis. Keep each line short and snappy; play a game of hot potato. And don’t forget to edit like crazy when you’re done. If you’re not removing bulk between those quote marks, you’re doing it all wrong. Even in my short examples above, I went back in and cut the detritus. Because good dialogue should flow, not lay inert like a dead body on some old science fiction TV show.

Similarly, characters should all sound distinct from one another. Don’t give them so many affectations they no longer sound realistic, but look, not everyone talks the same, do we? We have accents and ticks and odd regional slang we depend on. Try speaking your dialogue aloud as you’re writing it. Kind of helps to clear out the mental cobwebs. If you can hear it from your own mouth, and it sounds pretty good to you, odds are it’ll work well enough on the page.

The truth is, most readers depend on good dialogue to communicate story. You can build or establish character relationships with it, key in on essential plot points, foreshadow upcoming events, or just plain have fun and make people laugh. One more time, dialogue is the melody of this music we call storytelling. So make sure yours is enjoyable to listen to. Speech, language, it’s the engine that drives everything we do. It binds us together, tears us apart, and isn’t that the essence of story?

If you’re struggling with this, the old adage, practice makes perfect, is as always the essential factor. You’ll thank me once you’ve mastered this new superpower, and your readers will thank you. Is it possible to overdo it? Certainly. But wouldn’t you rather read a beautiful mess that sounds like Mozart rather than racoons rattling around in your trash cans late at night?

Heh. That’s a funny line. Maybe I should jot it down and have one of my characters say it someday. Until next time, everybody. Wooden conversation is as wooden conversation does.

Check out Jeff Bowles Central on YouTube – Movies – Video Games – Music – So Much More!

Exposition: Telling vs. Showing

Posted: January 22, 2018 Filed under: Books, Dialogue, Exposition, Fantasy, Fiction, Science Fiction, Writing | Tags: Exposition, Fiction, Show vs. Tell, Writing, Writing to be Read Leave a comment

A writer should show the reader, rather than tell the reader. Help them form a mental picture in their minds. Put them into the story. How many times have we all been told this? Finding a balance between showing and telling is a hard thing to do, but to be a good writer we must strive to achieve that balance.

I’m a person who likes to think big, and in my writing it’s no different. As many of you know, in graduate school, my genre fiction thesis project was the first book in my Playground for the Gods science fantasy series, In the Beginning. But, what you may not know is that my original thesis proposal was for what turned out to be the third book, only in my mind it was the only book and it spans back beyond prehistoric time. While preparing my thesis proposal the feedback that I recieved from instructors and cohorts time and again, was that my proposal would require too much exposition unless I created an epic tomb of unfathomable porportions, way beyond the scope of my thesis requirements, and impossible to complete in the time allowed.

The main problem was that there was a lot of background that I felt the reader needed to understand where the character was coming from in the now of the story. Most of that information was being communicated to my readers through exposition. The story wasn’t taking them back to relive the scene, it was simply filling them in on what they needed to know, because the story I wanted to tell spanned over billions of years. That’s a lot of backstory. That’s exposition.

Robin Conley saw a similar problem in her review of the movie Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice, “Almost all of these really big elements deserved a proper set up because they are major story parts that will potentially carry over… The long exposition and set up in the film makes the story drag and hard to stay involved, no matter how many interesting elements there are.”  Robin explains what exposition does and why we don’t want too much of it. Too much exposition is like coming in in the middle of a film you’ve already seen, and filling in other viewers on what is happening, instead of letting them watch the film and figure it out for themselves.

Robin explains what exposition does and why we don’t want too much of it. Too much exposition is like coming in in the middle of a film you’ve already seen, and filling in other viewers on what is happening, instead of letting them watch the film and figure it out for themselves.

That was the problem with my PfG story – way too much exposition. It happens all the time. And it’s easy to overlook it when you’re the author. Which is exactly what I had done with my thesis. I had that story outlined and plotted, but I kept having to stop and fill in the background details with exposition. And exposition tells your readers something, but it doesn’t provide a mental image for them. It doesn’t pulace them in the scene. Action and dialog accomplish those tasks quite well. And my cohorts and instructors were right, although at the time, I didn’t want to believe them.

My solution was to turn my story into a four part series. Hence the Playground for the Gods series was born. All that backstory, which had come out mostly in exposition, became a story of its own, one that I could show my readers, rather than telling them about it. My original story idea will eventually be book three, and although I did have to write the whole first book instead of the story I set out to tell for my thesis, that story outline is still waiting for me to put it in story form.

Of course, that isn’t the only way to solve problems of exposition, but this can be applied without creating entire novels. You simply expand on some scenes to eliminate exposition and create a longer story, chosing those scenes that are most vital to the story. You can also chose to leave certain information out, thus eliminating exposition without lengthening, and perhaps even shortening your story. It is a delicate balance, but as the writer, you must do what the story needs to achieve it. What works for one story may not necessarily be the answer for another.

So, how much exposition is too much? That’s a very subjective question, but generally speaking, if you’re telling your reader what happened, with a few lines of glib dialog thrown in here or there, then you have too much exposition. Your reader wants to get lost in the book, and for that, they need a story that is told in such a way that they feel like they are there.

We’ve all read stories like that. For me, it’s Anne Rice. I may have never been to New Orleans, but after reading some of her books, I feel like the Garden District and the French Quarter are old frieinds. I can smell the magnolia blossoms, and see the old plantation houses as if I’d been there. That’s the kind of story we, as authors, strive to write, regardless of the genre we write in. It’s the kind of story that has the perfect balance, using exposition only when absolutely necessary to fill in details, providing plenty of action and dialog to fill in the rest. It’s a delicate balance, but one we must all strive for.

Until next time, Happy Writing!

Like this post? Subscribe to Writing to be Read for e-mail notifications whenever new content is posted or follow WtbR on WordPress.

Dialogue: Talking in Subtext

Posted: January 30, 2017 Filed under: Dialogue, Writing | Tags: Dialogue, Subtext, Writing 3 Comments

A good way to learn to write good dialog is to become an observer of people, watching and listening to the conversations around you when in public. You must both watch and listen because dialog doesn’t come just in words. Dialog also contains subtext. You know, body language, tone of voice, etc… You can have whole scenes where no words are spoken, yet a conversation occurs between two people in the subtext of their body language. Everyone in the real world talks in subtext. If you want to have believable dialog for your characters, they must talk with subtext, too.

Whether you’re an author or a screenwriter, it’s an important concept to master. Subtext is the message that lies beneath the message. It’s what people, or characters, are really saying. It is indicated in actions, movements, change in pitch of the voice. A character may say, “I’m happy for you”, but if it were said through gritted teeth, the reader may get the idea that there’s some underlying resentment with the characters words, lending a very different meaning to the scene. The same dialog would take on a whole other meaning, that the words are not spoken sincerely, if the character rolls her eyes as she says it.

We humans are funny creatures. Many of us have some type of mental block that prevents us from saying what we mean outright. It may be the fatal flaw of mankind in the communication realm, although I suspect it may be easier to speak honestly in the digital world, where you talk with people without being face to face. Regardless, if you want your characters’ dialogue to be believable,they will have to speak in subtexts, offering readers the subtle clues necessary to figure out what is really going on.

“Don’t tell me to calm down,” Karen said, tapping her newly painted nails on the table top. “I’m perfectly calm.”

What can you tell from the dialog above? The character says she’s not upset, but do you think she is? Rather you get the idea that she is upset from the tapping of her nails on the table, which is not a calm behavior, even though her words claim different.

The example above is pretty clear for illustration purposes. In real life, and in good fiction, it’s not always so easy to discern between words and actions. As authors, we must offer good clues, in the form of subtext, so readers can see the whole picture we’re trying to paint with our words. You see what I mean?

If your character is angry, you might have him clench his fists or stomp his foot. If the scene is a breakup, your character may hold back her tears and swallow the lump in her throat to avoid revealing how much she is really hurting. Or maybe she is trembling although trying to appear brave to her friends.

If your character is angry, you might have him clench his fists or stomp his foot. If the scene is a breakup, your character may hold back her tears and swallow the lump in her throat to avoid revealing how much she is really hurting. Or maybe she is trembling although trying to appear brave to her friends.

It’s the way real people talk. It’s the way our characters need to talk if we want our dialogue to be convincing. In many cases, the old adage is true, especially in fiction and screenwriting- “Actions speak louder than words.”

Like this post? Subscribe to email to receive notification to your inbox each time a new post is made.